Andy Murray. “There were times when I couldn’t tie my shoes, when I thought I would never play again”.

“I could have been one of those children. Brothers and sisters of some of my friends were killed...”.

Andrew Barron Murray (Andy Murray in the sporting world) was eight years old on 13 May 1996 when Thomas Hamilton, 43, a former Boy Scout leader at Dunblane Primary School, a Scottish town of 9,400 inhabitants 65 kilometres from Edinburgh, burst into the gymnasium and opened fire with several revolvers, killing sixteen boys - most of them five years old - and a teacher. Twelve other children and three adults were wounded. He then killed himself. Andy and his brother, Jamie, were there and survived.

For twelve years as a tennis pro (since 2005), Murray avoided talking about the massacre. He was mortified inside. It was only in 2008, at the age of 21, in his biography ‘Hitting Back’, that Murray got it off his chest. He confessed that he and his brother (a year older) were on their way to the gym that day and when they heard gunshots, someone came over to check what was going on, after which he frantically returned and demanded the group run to the principal’s office. They hid under a desk. Terrified, the teachers had the courage to smile at the children and ask them to whisper songs until they could leave the room.

“We knew that guy (the killer). He once got into my mother’s car. It’s weird to think you had a killer in your car, sitting next to your mum,” Murray expanded, tormented. Indeed, sometimes Judy Murray would drive him from the Boy Scout camp to the train station. He had never been seen as dangerous.

Novak Djokovic, top-ranked tennis player and raised in the Belgrade of the former Yugoslavia when NATO forces were bombing souls, never fails to remember that the art of the racquet “saved his life”. For Murray (1st in the world on 7/11/2016 and at the top for 41 weeks) tennis was (is) also more than a sport: it was (is) an escape route.

“Dunblane happened when I was almost nine years old. Twelve months later, our parents divorced. It was a difficult time. And shortly after that my brother left home. We did everything together, so it was hard for me. For more than a year I had a lot of anxiety. When I was older, competing, I had breathing problems. But the anxiety disappeared when I played tennis. Tennis allowed me to escape. That’s why it’s so important to me,” says the Briton in the documentary ‘Andy Murray: Resurfacing’, released in November 2019. And there you understand a lot of things.

A sanguine, ambitious and acid tennis player, with a brilliant reading of the game, great athletic ability to defend and counter-attack and with a return of the highest order, Murray was - for years - one of the artists of the Big 4, with Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Djokovic. He is the only one with at least seven victories over the Swiss, the Spaniard and the Serb. Winner of the 2012 US Open; first British Wimbledon champion in 77 years (in 2013; he repeated in 2016), since Fred Perry did it in 1936; winner of the 2015 Davis Cup; and the only one with two Olympic singles gold medals (London 2012 and Rio 2016). He was stopped only by his battered hip.

The pain, unbearable, led him to step away from the tour after Wimbledon 2017, when he couldn’t even tie his shoelaces. He underwent an initial surgery in January 2018 and returned to play in mid-June of that year, after 342 days of inactivity. But he did not improve, and in January 2019, before making his debut in Australia, he broke down during a press conference and announced that his retirement was imminent because he could no longer tolerate the discomfort. On the 28th of that month, he was back in the operating theatre: he underwent a hip reconstruction, in which a joint was removed and replaced with a metal implant. British doctors went so far as to say that Murray should settle for improving the quality of his daily life and play tennis recreationally or evaluate coaching. Ranked 324th, he returned to play in August in Cincinnati. He continued to compete in dribs and drabs and dropped down a level to a Challenger in Mallorca, but in October he felt revived. At the ATP in Antwerp, Belgium, he was crowned champion (the first title in 31 months, an eternity for a player of his category). It was his last trophy. Due to back problems and the cancellation of the tour because of the pandemic, he played only seven matches in 2020.

This season he has played ten matches (five of them in a Challenger) and, although he is living with a groin discomfort, almost miraculously he is not thinking about retirement. A few days ago, as 124th on the tour, he competed in the prestigious Queen’s tournament (his first grass-court event since 2018) and broke down in front of the microphones again, after beating Benoit Paire. But this time his eyes were not wet with sadness, as they were in Melbourne 2019: he was moved by having been able to expel his demons, for having returned to doing what he has loved since he was a boy (he then lost in the 2nd round to Matteo Berrettini). Tomorrow the curtain will rise at Wimbledon and he will be one of the 128 players in the main draw: he received a wild card and will make his debut against Nikoloz Basilashvili. He is 119th and hasn’t competed at the All England since 2017, when his hip ended up popping.

“I don’t want it to be my last Wimbledon. That’s not my plan. I don’t want to be at the tournament thinking I’m saying goodbye. I want to keep playing,” Murray warned at a press conference. But in the midst of the London maelstrom and preparations for the third major of the year, he agrees, for the first time, to embark on an exclusive chat with LA NACION. Lucid, reflective and sharp.

-How would you illustrate the process in between the tears of grief in Australia 2019, when you thought you could never play again, and the tears of joy, having played a few days ago at Queen’s? What has the journey between one extreme and the other been like?

-I’m sure it’s been a tough couple of years. There were times when I couldn’t put my own shoes on because my hip hurt so much and I really thought I would have to retire at that point. Australia was extremely emotional: tennis has been my whole life and it looked like I was going to have to give it up. I didn’t know what the future would hold. To be back on the court now feels great. I worked hard to get here, with the rehab and training, and I feel good physically again. There were times when I thought I would never play again, so playing and winning games feels very special.

// // //

Murray (34) and Juan Martin del Potro (32) are sixteen months apart. They played against each other as juniors [clear victories for the Scot at the 2004 US Open and 2005 Roland Garros], the relationship between them was tense from the start and, as professionals, it worsened in Rome 2008, when they argued in a match, the Argentinean said “You’re always the same. You and your mum”, and the umpire intervened to try to calm things down. But everything changed in 2010, during Juan Martin’s dark period after his right wrist surgery. At that time he received messages of support from his colleagues, including Murray. Since then, they have gone from a prickly bond to building an adult friendship, with shared sufferings.

-Where do you and Juan Martin find the strength not to give up?

-I think you find the strength to keep going because you love the game. Certainly that’s my motivation and I think there’s always the feeling that you’re not ready to give up yet. I can’t speak for Delpo, but he showed real strength and determination to keep going when he had repeated problems with his wrist and I’m sure that was driven in part by his love of tennis.

-In 2016 you played two historic matches with Del Potro: in the Olympic final [the European’s 7-5, 4-6, 6-2, 7-5 win] and in the Davis Cup semi-finals in Glasgow [the Tandilense’s 6-4, 5-7, 6-7 (5-7), 6-3, 6-4 win]. From a distance, how do you remember each match?

-Both were exhausting matches. The one at the Olympics lasted more than four hours and in the Davis Cup it lasted more than five hours; they were pretty intense. In Rio, obviously a lot of people were behind Delpo, but I was determined to defend the Olympic gold medal I had won in London. He played a great match and it was close until the end. Fortunately I was able to take the win. The Davis Cup match in Glasgow was another tough on-court battle. Obviously I had the crowd on my side this time, but he played better that day. I think he was pretty motivated to win after the Olympics.

-You generally get involved in issues that many elite athletes find uncomfortable or silent, such as gender diversity, racism, domestic abuse, distributing money to help players in need, etc. Why does it motivate you to do so? You are aware that the weight of your voice can make a difference, at least in sport, right?

-Yes, I think it’s important that if you have a platform you use it to speak out about the things you believe in. I’ve been known to be outspoken on certain issues, but I see things quite clearly when it comes to feminism or racism. Everyone should have the same opportunities. Of course I will speak up if I think something bad is happening.

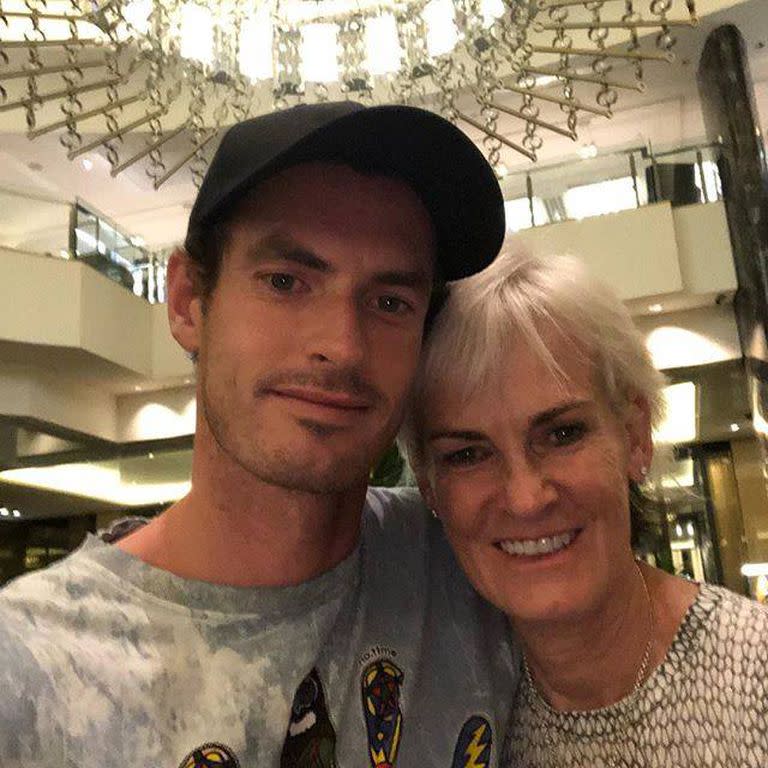

-You had a strong influence from your mother in your upbringing and career. Is the sensitivity you show as a person because of her?

-Certainly my mum [tennis coach] was instrumental in defining my career, but my dad [Will] and my grandparents also played a big role. They always encouraged us to show our emotions and I think that’s healthy, especially as a man.

-In a 2019 interview you said that to your “dream dinner party” you would invite Ricky Gervais (actor, comedian and screenwriter), Barack Obama and Muhammad Ali. Why would you do that in each case?

-Muhammad Ali has always been an inspiration to me, for what he did in and out of the boxing ring. I would love to ask him about competing as a black man at the time and how he found life being the most famous athlete in the world of his time. Barack Obama is such an eloquent and interesting person, and he has a great sense of humour - who wouldn’t want him around a dinner table? And I think Ricky Gervais would make me laugh all night. I love his work and have been a big fan of his for years.

-We see that you have other business activities outside tennis, including a hotel in Scotland, in Kinbuck, 3 miles from Dunblane, where you grew up. At the time, your mum said, very amusingly, that she tried to talk you out of buying the castle because it was “falling apart” and had bats in it. Why did you get involved in that?

-I bought Cromlix in 2013, the hotel was about to close. My family lived near the hotel and it provided a lot of jobs for people in the local area; I felt it was important to keep it open, so I took it on and we did a total renovation, so it’s now a five-star property, with a restaurant. It’s where Kim [Sears, his wife; they got married in 2015] and I had our wedding reception. I try to go up there whenever I can, as it’s a beautiful place.

-Aside from your connection with several South American tennis players, you travelled to Barcelona at the age of 15 to improve your Spanish at Emilio Sánchez Vicario and Sergio Casal’s academy, but learning to speak Spanish is one of your unfinished business. Do you think you have time to learn it?

-I would love to learn Spanish; I learned some when I lived in Barcelona and I understand more than I can speak, but it’s very rusty. I don’t have much time at the moment, with tennis and four kids! [NdR: Andy and Kim had their fourth child in March]. But I hope to learn more when I retire.

-You’re a big football fan, you might have played for Glasgow Rangers as a kid and you have a lot of references to Argentinian football. Last November you made a post after the death of Maradona, who you met at the London 2010 Masters. How did you feel about the tragic news?

-I was saddened to see the death of such a legend. He was one of the greats of football and he died before his time. I met him once, as I said in the Instagram post, and he had such a charismatic personality; I can see why he had such an impact on the game.

// // //

Murray carried the weight of history on his shoulders for years as Britain remained without a champion of its own at Wimbledon. He endured unbreathable pressure and being disparagingly referred to as a Scot if he lost and a Brit if he triumphed. In 2012, when he lost the All England final to Federer, he broke down in front of everyone, triggering a profound emotional change. In the face of crowds who saw him as a moody, cold character, he became more human. It liberated Andy. So much so that a few weeks later, on that very same turf, he won the Olympic medal. And a year later he would break the local jinx at Wimbledon, winning the golden trophy. His recognition was such that in 2019 he was knighted by Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace for his contributions to tennis and commitment to charity.

-Andy, do you remember what you thought about the first moment when you stood alone in front of a mirror after winning Wimbledon in 2013 and shed the weight off your shoulders?

-Actually, it was a really surreal moment for me. Winning Wimbledon was what I worked for my whole life, so to have achieved that goal felt really strange. I don’t remember much about the match [vs. Djokovic 6-4, 7-5, 6-4] or the immediate aftermath because I think I was pretty dazed, so in the days afterwards I just tried to reflect on what had happened. I found I enjoyed the 2016 win more because I made sure I took stock of what was going on and enjoyed the moment more.

-In 2013, after Wimbledon, you were the subject of one of the best sports photographs in history, later replicated on the front page of The Times. It’s very symbolic because it’s as if you’ve been freed from the pressure of the public for once. What did the image mean to you? Do you have it framed? Did you know Julian Finney, the photographer who took it?

-Actually, it’s good to have that picture, because it helps me remember that day and the moment I won. I didn’t really think about what I was doing when I climbed through the crowd, I just wanted to reach out to my family and my team, as they had been a big part of me becoming Wimbledon champion. I have the photo framed in the offices of my company, 77 Sports Management, where we represent and advise emerging tennis players and footballers.

-Titles and technical/physical prowess aside, is the common thread among the Big 4 the love they have for the game of tennis? Are they sustained by the passion they possess?

-Yes, I think passion is a common factor. I think there is also a common work ethic and approach that maybe other younger players don’t have in the same way.

-You played at Wimbledon for the first time in 2005 [3rd round loss to David Nalbandian] and now you’re returning for the first time since 2017. What are your feelings?

-I had a lot of problems in the last few years, injury problems. I prepared a lot for this and it will be a big mental challenge. When I step on the court and play it will be very different, I will compete for every point and if my body hurts afterwards, it will be fine. In 2005 I was a bit nervous. Now it’s different. I was looking forward to coming back, I missed the pressure. Tennis is something I’ve done all my life and I want to continue on this journey.

Yahoo Noticias

Yahoo Noticias